May/June 2017

Bias in the Engineering Workplace

BY DANIELLE BOYKIN

* Members quoted in these articles were allowed to remain anonymous and given fictitious names, due to the sensitive nature of the issues.

Women and people in nonwhite ethnic and racial groups are a growing part of the US population. Yet, the participation of women, blacks, Latinos, Asians, and Native Americans in engineering and other STEM fields remains woefully underwhelming, according to National Science Foundation data. There are expanding efforts to encourage and support the entry of more women and people of color into the engineering workforce, but there is a significant challenge to the recruitment and retention of diverse talent that can’t be ignored.

Women and people in nonwhite ethnic and racial groups are a growing part of the US population. Yet, the participation of women, blacks, Latinos, Asians, and Native Americans in engineering and other STEM fields remains woefully underwhelming, according to National Science Foundation data. There are expanding efforts to encourage and support the entry of more women and people of color into the engineering workforce, but there is a significant challenge to the recruitment and retention of diverse talent that can’t be ignored.

NSPE encourages diversity and supports equal employment opportunity and promotion opportunities for all engineers. The Society also encourages members and employers in each practice area to make special recruitment efforts that lead to adequate representation of minorities and women at all levels of the engineering profession.

A look back at an article published in May 1955 by NSPE’s American Engineer is a stark reminder of the barriers that women in professional engineering experienced. The article highlighted a Department of Labor “Employment Opportunities for Women in Professional Engineering” bulletin, which laid out the obstacles presented by the traditional prejudice against women in “men’s jobs” and how employers were reluctant to invest in the training of women who they believed would resign because of marriage or home responsibilities. According to the article, the Labor Department’s bulletin offered this advice: The responsibility for bringing about universal equality of opportunity for women in engineering employment will for some time to come lie with women engineers themselves.

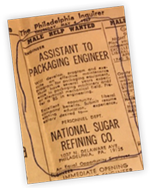

How much has the engineering workplace changed since that time for women and, now, people of color? Long gone are the days in which engineering firms shut out women with “male help wanted” ads. The presence of women in the engineering workforce has increased from 8.6% in 1993 to 14.9% in 2013, while more than 33% of this workforce is represented by people of color and Hispanics, according to the National Science Foundation. Yet, there is more outreach work being done to diversify the field.

In 2016, the Society of Women Engineers commissioned a workplace experiences study by the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California, Hastings College of Law, which reveals that women engineers and engineers of color continue to face bias and stereotypes. This leads to disadvantages in hiring, pay, promotions, performance evaluations, and mentoring and leadership opportunities.

The study, Climate Control: Gender and Racial Bias in Engineering, is unique, says Joan Williams, because it studied race and gender at the same time, while most reports usually study one attribute at a time. The researchers surveyed 3,000 engineers and engineering technicians and examined how the results aligned with decades of research on workplace environments. “Overall, both women and people of color, as compared to white men, felt that they had to prove themselves more in the workplace,” says Williams, a law professor and the center’s founding director.

When talented professionals feel that they are being deprived of opportunities or are being treated unfairly, they will leave, which can prove costly to engineering firms and organizations. “It’s very expensive for companies to have to keep hiring talent again and again, which doesn’t make good business sense,” says Williams. “Unless they are just going to say, ‘Okay, only white men thrive here, so we’re just only going to hire white men,’ which is illegal.”

Are You Qualified?

Changing an unwelcoming or even hostile environment will require engineering leaders to understand the types of biases experienced by women and people of color in the workplace. One of the most prominent types of bias documented in Climate Control is prove-it-again bias. This bias involves higher or double standards, and it stereotypes a group as less competent at engineering than the majority demographic of engineering in the US, white men.

Women and people of color experience this type of bias when others assume they are unqualified and hired only to meet a diversity quota. They are held to higher standards and must prove themselves before receiving the same level of respect that majority men automatically receive. Women who are pegged as not being a “good fit for engineering” experience disrespect or have their opinions or recommendations disregarded or mocked.

Climate Control participants reported that their expertise is ignored or discounted, and their work performance is overly scrutinized, while some ideas are discounted or credited to men if implemented successfully. Women engineers of color were more likely to report prove-it-again bias—71% of women of color versus 59% of white women.

NSPE member Jennifer*, P.E., first experienced gender bias while attending high school in the early 1970s. Jennifer had finished all the available math courses by her junior year. When she and another female classmate went before the local board of supervisors to request permission to take calculus at a junior college, they were denied the request and told that they wouldn’t need to use that math because they were female.

During her senior year, a teacher who oversaw a scholarship committee told Jennifer one of his guidelines for determining who gets a scholarship. “He told me that if it came down to a girl or a boy, he would award the scholarship to the boy because he will need to support a family one day,” she recalls.

NSPE member Nancy*, P.E., recalls leaving a company earlier in her career because of management’s lack of leadership and failure to prevent or correct a supervisor’s gender bias and discriminatory behaviors. Yet, she remains committed to the engineering profession after 22 years. “I have stayed because it’s the best use of my talents to make a positive impact on the health and welfare of people and the environment,” she says. “I [also] realize that the more women we have working together in the profession, the more inviting the profession will become for women. The same is true for all kinds of diversity.”

But it’s not women or anyone discriminated against who needs to change, Nancy believes. “I don’t think we should adjust to bias; the perpetrators of bias and discrimination should be expected to modify at least their behavior, if not their attitudes,” she says. “If they can’t, there should be consequences.”

Walking a Tight Rope

In traditionally male work environments, women face bias that forces them to constantly monitor and adjust their behaviors. According to Climate Control, women engineers are under pressure to exhibit just the right level of feminine behavior while having to be wary of behaviors traditionally associated with masculinity; this is known as tightrope bias. Women can also be expected to perform duties that are considered “office housework” and administrative tasks. In some environments, women who shun office-housework roles may face criticism and pushback.

Women engineers reported that they were less likely than white men to say they could behave assertively or show anger without pushback. Women were more likely than white men to report pressures to let others take the lead and were less likely to report having the same access to desirable assignments. Women, African American, and Asian American engineers reported more tightrope bias than male or white counterparts.

Donna*, P.E., is a professional engineer with 15 years of experience, licensed in several states. Yet, there are times when she isn’t taken seriously by some of her male colleagues. A coworker has mistaken her for a secretary, later apologizing for his “chauvinistic tendencies.” Another coworker called her a “typical impatient woman” in response to a comment she made. “I try to laugh off what I can when I can, and sometimes vent to others about the ridiculousness of it,” she says. “[Other times] I may avoid dealing with the comment and walk away.”

She adds, “It’s still taboo to talk about. I [worry] that if others know I complained about someone, they’ll avoid me for fear that I’ll complain about every little thing said.”

The Boys’ Club

Women who participated in SWE’s study commented that one of the biggest challenges they face is dealing with a “boys’ club” atmosphere. This involves trying to figure out how to fit in a predominantly male workplace and experiences of social isolation.

In her current position, Jennifer has discovered that she has a hard time providing guidance or input to a certain group of male engineers. “I am [deemed] disrespectful if I disagree or point out that they are incorrect, so I have enlisted the help of a male colleague,” she says. “It’s just amazing how well my ideas and comments are received when delivered with a deep voice. I am too old for this behavior and too tired to fight beyond what I have done to date.”

A boys’ club atmosphere—filled with gender bias—can stoke heightened conflicts and competition among women if they are made to feel that there are limited opportunities for women to advance (tug-of-war bias). The study points to research finding that women who have experienced discrimination early in their careers often distance themselves from other women or perpetuate bias by holding women to higher standards than men. This type of bias can also have racial components, with people of color distancing themselves from other people of color or holding higher or double standards and judgments about assimilation.

Brenda*, P.E., chose the engineering field because her father suggested it—she was good at math and always fixing or programming a computer or VCR. “Engineering would also provide a sense of job security, since I was fiercely independent,” she says.

That fierce independence would bolster her in the tough times of her 22-year civil engineer career. At one company, Brenda was the only female engineer in construction in a small town. She describes the bias she faced as “typical.” Groups of men stopped talking when she showed up; her supervisor failed to provide adequate training and made fun of her in front of her colleagues. She resigned on her one-year anniversary with the company.

That experience and others took their toll on Brenda. “I just shouldered the discrimination that I dealt with on a day-to-day basis—the comments on my appearance, the frat-boy jokes, and comments on how I should react in certain situations,” she says. “For many years, I had a real chip on my shoulder about being a woman in engineering and rejected all things feminine.”

Brenda realized that if she wanted to remain in the profession, she had to re-

evaluate her career path. She made it a priority to find a new company—with women in high leadership positions—that fit her needs as an individual and as a working mother. “My current organization supports my role in leadership in professional societies and especially the work I’m trying to do in diversity inclusion.”

Michael*, P.E., has been a licensed professional engineer since the late 1970s. He has seen a lot of the world around him change and advance, yet he is taken aback that engineering is still a profession largely white and male. And too many engineers, he believes, are okay with it. “The lack of diversity in the engineering workforce means there is a real lack of new ideas coming to the worktable,” he says. “It’s not that white men don’t innovate, but we are only a part of the total human population and our point of view is just by nature going to skew in a fairly narrow direction.”

He adds, “While I’d like to believe that I can try to look at problem solving like a woman might, or an African American or Latina, I know I truly cannot. If I hire a diverse group of people to do that thinking and listen to them, I solve that problem to a great extent.”

Although Michael hasn’t been a target of bias or stereotyping, he has left companies that didn’t treat women engineers, engineers of color, or gay engineers fairly. “The most significant problem I have faced was because I hired and mentored women engineers,” he recalls. “People didn’t come directly to me and make trouble, but they did treat the women I mentored very badly and accused them of inappropriate behavior.”

The most difficult part, he remembers, was leaving behind those engineers in bad situations. “I tried my best to help most of them to transition to better [organizations],” Michael says. “Since the teams I built were successful, because of the different ideas and approaches we used, their resumes usually benefitted.”

Motherhood vs. Career

Women, no matter the profession, have had to contend with societal beliefs on how they should juggle their careers and family obligations. Professional women experience career pressures and negative criticisms and judgments not faced by their male peers who become parents. Climate Control describes this type of gender bias as maternal-wall bias. Some women even reported that they didn’t experience gender bias until they became mothers.

Comments provided to the survey researchers revealed that some women felt a need to “work harder” to reduce assumptions that that they couldn’t work at the same competency level. Other participants reported that they were either expected by supervisors and colleagues to work less hours or were passed over for critical work assignments after becoming parents.

Carol*, P.E.—a woman in her 30s—recalls the recent maternal bias she received from people who thought she wouldn’t be able to continue the same commitment to her career upon learning she was having her first child. “I was so often asked, ‘How are you going to keep up with your travel schedule once you have your baby?’” she recalls. “[My husband] travels as much, if not more than I do, yet no one ever asked him that question. But I was asked repeatedly. Most people wouldn’t ask a guy that question.”

Changing the Climate

If an organization’s leadership knows it has a workplace climate that is problematic for women, people of color, and members of the LGBTQ community, Williams, of the Center for WorkLife Law, advises them to look beyond standard diversity programs. “Just founding a women’s initiative or an employee resource group for engineers of color, while positive, isn’t going to solve the problem,” she says. “If you have a diversity problem, it’s because you have implicit bias constantly being transmitted through your basic business system—through hiring, performance evaluations, and assignments.”

Williams has used her research to develop a program (biasinterrupters.org) to help organizations root out bias. The program enlists a three-step process of using metrics to pinpoint bias, implementing actions to interrupt the bias, and returning to the key metrics to see if there is any change. For example, a company could use the following questions in performance evaluations to help provide key metrics for improvements:

- Do your performance evaluations show consistently higher ratings for majority men than for women, people of color, or other relevant groups?

- Do women’s ratings fall after they have children?

- Do the same performance ratings result in different promotion or compensation rates for different groups?

Michael is adamant in his belief that a diverse engineering workforce—void of discrimination—is needed to improve the profession. In previous leadership positions, he implemented intensive training when necessary to help reduce discriminatory conduct and bias within his firms. “I think some of these things worked, but the problem was that it took time, and often the people who were subjected to the bad treatment just left.”

He is also hopeful that a new generation of women engineers and engineers of color can tap into more resources and support systems, both inside and outside of their organizations, to overcome challenges brought on by bias. “People who are different from white males are not competition,” he says. “They are a source of ideas and energy that should be welcomed into our profession to make it vibrant and relevant.”

Overlooked Talent

African American women outnumber their male counterparts in pursuing degrees in US universities and colleges, yet these numbers aren’t reflected in engineering degree programs. A new report calls on the engineering profession to target outreach to African American women to fill growing STEM talent gaps.

The report, Ignored Potential, points out that despite the significant number of African American women enrolled in college, they lag behind their male peers in pursuing engineering degrees. Less than 1% of all US bachelor degrees were awarded to African American women in 2015, according to the American Society for Engineering Education. This could hamper the STEM profession’s programs, as jobs in this sector are projected to increase by 10% by 2020.

Why aren’t more African American women choosing engineering as a career option? The research points to several reasons: lack of visible role models in universities and in the field, stereotype threat, marginalization by the dominant culture, tokenism and isolation within organizations, and pay inequities. Researchers also believe that African American women “get lost” in programs designed to reach out to women and people of color.

The report, released in March, was commissioned by the National Society of Black Engineers, the Society of Women Engineers, and Women in Engineering ProActive Network. These organizations believe that more can be done to ensure that African American women are no longer invisible and can successfully participate in STEM fields.

The report offers the following recommendations to help organizations and industry improve outreach initiatives and inclusion programs:

Professional Organizations

- Provide for joint memberships in organizations that have meaningful intersections. NSBE and SWE offer joint membership at a discount for their members. The organizations can also collaborate in programming, outreach, and with other institutions.

- Provide opportunities within annual meetings for researchers to highlight work that uses an achievement-based framework. Arrange cosponsored programs within larger events of engineering societies to demonstrate that multiple identities of African American women can coexist.

- Provide information on how members can get involved in service work, advocacy, and other educational opportunities related to issues that affect them personally.

- Highlight the success stories of members who can serve as intersectional role models to other individuals within the organization. Networking events, awards, and newsletter articles can provide a space for African American women to connect.

Engineering Industry

- Partner with organizations to support K–12 and college initiatives to increase interest and retention in STEM.

- Actively recruit talent at historically black colleges and universities, which graduate the most African American women engineers.

- Establish active mentoring initiatives to encourage networking and stronger feelings of belonging among employees.

- Implement training that equips employees with the means to recognize their own stereotypes and bias to help create a safe space for those who may feel undue pressure.

- Review hiring and promotion processes to ensure that the company offers fair salaries and opportunities. Make adjustments if discrepancies are detected.